Oracle Extractable Value in Compound: A Risk Perspective

I want to start by thanking everyone who contributed to getting OEV up and running on Compound. Thanks to @Kyle from AlphaGrowth and @ugurmersin from API3 for their original proposal back in Feb and also to @mattgurbiel, @mikemassari, @Thogard, @jacob_fastlane and the RedStone and FastLane teams along with @AshNathan and @Chainlink_Labs for their proposals as well.

I also want to thank @PGov and @AranaDigital and the Compound Governance Working Group for streamlining the vendor selection process and @woof, @jbass-oz and the OpenZeppelin team and @Gauntlet for their detailed analyses on the topic. This is an important step forward for Compound.

As Compound considers adopting an OEV solution, Platonia shares Gauntlet’s view that the focus should extend beyond potential revenue to include protocol safety, risk management, and architectural soundness.

We’ve reviewed the proposals and conducted a quantitative analysis on OEV. This post outlines our perspective from a neutral, risk-first lens to help the DAO make an informed decision.

Why OEV matters, but should be kept in context

OEV is a symptom of an architectural inefficiency in how lending protocol conduct liquidations.

In their current form, liquidations are a highly inefficient form of risk reduction

- They overpay for protection when the benefit is marginal (e.g. small or low urgency liquidations etc)

- They firesale large amounts of capital in a public and highly exploitable manner, often at the worst possible times during peak market turmoil and incur maximum execution costs

The first issue calls for a calibrated design for dynamic liquidation penalties. The second requires better mechanism design for executing risk reduction in the market.

OEV solutions auction off the right to recapture this inefficiency and return a portion of it to the protocol. These probably do reasonably well on (1) by forcing searchers into competitive bidding but perform poorly on (2) and make the problem worse (analysis below).

It’s encouraging to see community excitement around OEV (we’re excited too). It likely represents a revenue improvement over the current state.

However, OEV recapture is not a structural fix. The long term goal should be to design liquidation systems that minimizes this value leakage in the first place.

The DAO should treat OEV as an interim optimization, not an essential feature. Decisions should be made with caution, avoiding unnecessary risk introduction while the community works towards more robust and efficient liquidation design.

Key risk considerations

OEV solutions introduce more insolvency risk

In their existing form, OEV auctions add costs for liquidators without reducing underlying protocol risk. This strictly decreases the likelihood of timely liquidations under current conditions. Additionally, the time required to run an OEV auction can introduce delays which Gauntlet has shown to be costly in their risk analysis.

Empirical liquidation delays from OEV

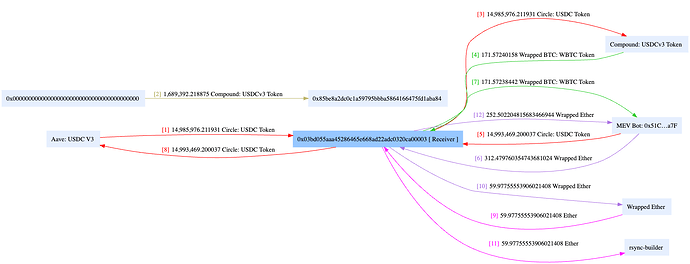

The largest real world instance of OEV on Compound III occurred during the Mantle liquidation on February 3.

Roughly 20% of the liquidation incentive was lost to slippage costs in the cmETH/USDe and cmETH/mETH pools on Agni. Another 40% went to Compound via the storeFrontPriceFactor (SFPF). The remaining 40% (about 76k MNT valued at ~$65k at the time according to API3’s MNT/USD oracle) was captured by API3’s OEV oracle.

A closer look at market conditions during the liquidation highlights several worrisome details.

First, both the Chainlink and RedStone oracles updated to a ETH price below the eventual API3 liquidation price 27 blocks earlier, resulted in a 40s liquidation delay relative to alternate feeds. By the time the liquidation occurred, the stale API3 oracle liquidation price was more than 7% above the market and marked to what was reported by the other oracles, the 1.5M account was already 10k insolvent. In the 40s leading up to the liquidation ETH had dropped >10%, which would have resulted in an insolvency loss of 160k had the same drop persisted.

Another point of serious concern is that Compound was very fortunate that the Agni pool implied ETH price was trading above the oracle price during this time period. Had arbitrageurs traded the Agni pools in line with the broader market, it’s possible that the liquidation incentive may have been insufficient to cover the slippage given that the ETH pool price went from 2600 to 2050 during the liquidation, which would have introduced substantial insolvency risk.

While the outcome was ultimately favorable, it underscores how fragile and path dependent the current system can be.

This isn’t meant to single out API3 and @ugurmersin has already given context on the delay here. However, it’s difficult to view this as a positive data point for API3’s OEV record on Mantle. This could have easily resulted in a sizable insolvency and it’s unlikely that such favorable arbitrage conditions would have existed had this occurred on more liquid ecosystems such as Ethereum mainnet, Arbitrum or Base.

Increased liquidator costs leads to liquidation delays

Deviation between DEX and oracle

The Mantle example highlights a key issue in liquidator costs that arises from deviations between the oracle price and the DEX price of the collateral relative to the borrow asset.

Oracles aggregate prices from both centralized and decentralized exchanges. While DEX prices are usually well-arbitraged onchain, CEX-DEX arbitrage is slower and more complex. During sharp market moves, this can result in meaningful spreads between the two.

As a simplification, suppose the oracle reflects a weighted median of DEX and CEX prices. In the case where \text{CEX price} < \text{oracle price} < \text{DEX price} the protocol ends up quoting the collateral too cheaply relative to what is available on DEXs. This gives the liquidator an opportunity to arbitrage both legs of the liquidation and extract additional profit. In such cases, the liquidation incentive is overly generous since the liquidator would likely participate even without it.

More commonly, the reverse situation occurs where

\text{CEX price} > \text{oracle price} > \text{DEX price}. Here, the deviation works against the liquidator by directly reducing their expected profit. This can make the incentive insufficient to cover slippage, reducing OEV recapture and increasing the risk of liquidation delays.

Empirical data

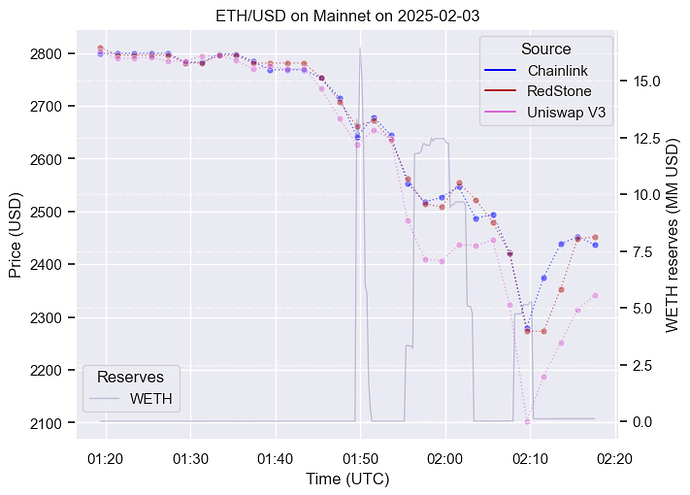

This dynamic was clearly visible on Feb 3 as highlighted in Gauntlet’s analysis.

Plotting protocol WETH reserves [1] and market conditions following the large absorptions gives

A significant amount of absorbed WETH remained unliquidated across multiple time periods. A key reason is that the Uniswap V3 price was 4-8% below the oracle price at times, making it too costly for liquidators to offload collateral into the primary DEX liquidity venue when the WETH liquidator incentive (post SFPF) was only 3%.

In contrast the WBTC absorbed [2] was liquidated instantly

as the Uniswap V3 price was roughly in line with the oracle at the time of liquidation.

Race conditions for large liquidations

Large liquidations tend to be highly correlated across lending protocols. Since liquidators draw from the same onchain pools, this creates a race condition where protocols compete through incentives to have their positions be liquidated first. Being second (or later) means worse execution and higher insolvency risk.

On February 3, Aave and Compound III experienced large volumes of liquidations. A likely reason WBTC was liquidated quickly on Compound is that the liquidator incentive was 6% compared to 4.5% on Aave. The subsequent drop in Uniswap V3 price relative to the oracle was likely driven by additional WBTC liquidations on other protocols. The large Compound liquidation had already removed a significant amount of liquidity, setting off a broader dislocation.

In contrast, the ETH liquidation incentive was 4.5% on Aave and only 3% on Compound. This made Compound’s ETH liquidations less attractive, especially when multiple protocols are competing for the same liquidity, which contributed to delays.

Transaction inclusion and ordering are critical during fast-moving market events. OEV auctions reduce the amount liquidators can pay in builder tips, making their transactions less competitive and increasing the risk of failed or delayed liquidations.

OEV revenue is overestimated

Platonia traced the 10 largest absorptions in Compound III’s history and the corresponding ~50 large liquidations that followed, totaling 170M which is approximately 43% of all lifetime absorption volume. Our findings indicate that only a small fraction of liquidation incentives can be safely recaptured by the protocol (<5% for large liquidations).

Slippage costs dominate large liquidations

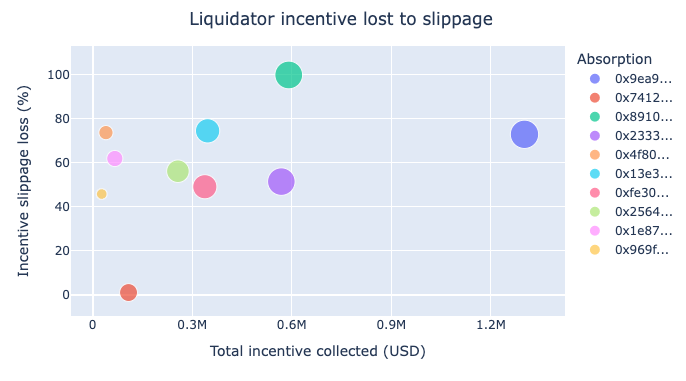

A more detailed breakdown of liquidation costs can be found here but empirically liquidators have spent the majority of the incentive themselves paying astronomical slippage costs to dump the exposure on DEXes within the same block. This can be seen below

where 68% of the total incentive collected by liquidators was eaten by slippage costs.

A particularly egregious example was the largest liquidation (buyCollateral event) in Compound III. This was nearly $20M in size with a total incentive of $591k.

Of this, ~$589k went to slippage leaving just $1.4k for the builder tip and $0.3k to the liquidator, with only 5 bps of the incentive pocketed by the liquidator.

Large absorptions are often not repurchased immediately

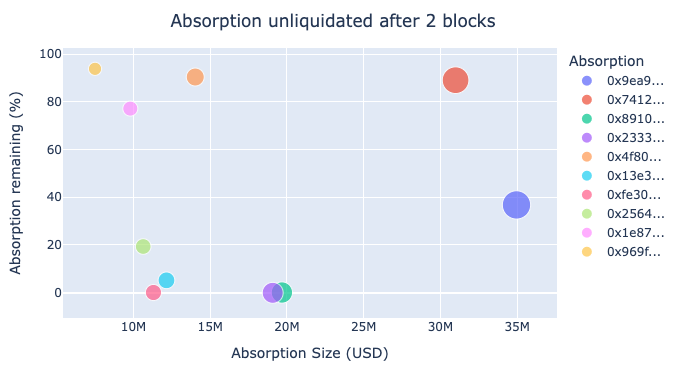

As Gauntlet has previously alluded to, absorbed collateral often experiences delays before being fully liquidated. As shown below

41% of the total absorption volume remained unliquidated after 2 blocks.

While the core issue is insolvency risk, the longer it takes to recapture OEV, the noisier the outcome becomes e.g. collateral prices may recover causing the liquidation opportunity to vanish.

Everyone takes a cut

It’s worth noting that Compound III already captures a significant share of the liquidation incentive through the SFPF. This is set to 60% for the mainnet USDC and USDT comets where the dominant majority of liquidation volume has occurred, making the protocol’s current cut ~40%.

From there, the aforementioned slippage costs are effectively deterministic from the atomic liquidator’s execution strategy so recaptured in the auction and comprise a hefty chunk.

What’s left is split between builder tips and liquidator profits, of which the proposed OEV provider fees range from 20 to 45%.

This accounts for just 0.68% of large absorption volume as shown.

Builder tips also present a tricky counterfactual. They are difficult to fully recapture, as reducing them could affect the transaction inclusion in the first place and cause liquidation delays and heightened insolvency risk.

In effect, the benefit of OEV in this context is likely comparable to reducing the SFPF from 0.6 to 0.5 on the mainnet USDC and USDT comets, but without the integration overhead or added security risk.

Atomic liquidator profits are small

Atomic liquidators are myopic, profit seeking bots who will perform liquidations for miniscule amounts of profit. Thus, cutting into their profits through auction bids is a safe way to redirect OEV to the protocol without leading to much additional protocol risk.

Unfortunately, only 4.7% of the total incentive collected was liquidator profit.

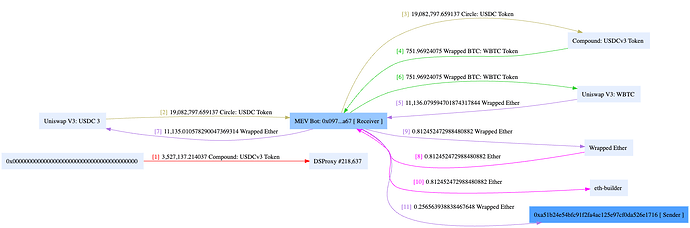

As an example, looking at the largest absorption in Compound III history

This was a $35M absorption with $790k of slippage costs, a $158k tip to the builder, $7.5k to Aave for a flash loan and the liquidator pockets basically nothing (maybe like $5).

OEV reflects an underlying design flaw. Better alternatives exist

OEV is only relevant because current liquidation mechanisms are highly wasteful in execution. Initiatives like partial liquidations improve the efficiency of risk reduction, making Compound more competitive by enabling lower liquidation incentives and higher collateral factors. Implementing such improvements would naturally drive OEV extraction toward zero. By contrast, OEV solutions that heighten insolvency risk make Compound less competitive, trading long term growth in exchange for some short term revenue.

Empirical data

A clear example of inefficiency can be seen examining WBTC reserves and the market conditions around the largest absorption on Optimism.

Despite an exceptionally generous 10% liquidation penalty for an asset that is essentially BTC, the $2.4M liquidation took ~20 blocks and was executed gradually. The liquidator dumped the entire position into Uniswap V3, depleting liquidity and pushing the pool price nearly 7% below the oracle.

An OTC desk could likely have quoted and executed this risk for a few basis points. Instead, the full incentive was consumed in DEX slippage. This liquidation should have been both immediate and cost-efficient, but without a redesign of the liquidation system, it remains difficult to incorporate even basic trading intelligence. That gap continues to hold back the protocol’s competitiveness.

Liquidation inefficiency

One of the most important tenets of U.S. electronic equities is Regulation NMS, which enforces order protection to prevent trades from being executed at inferior prices. By contrast, the current liquidation process in DeFi resembles a standalone exchange posting large, unprotected orders several percent through the market book, waiting to get ripped off.

This design, which results in large, binary liquidation events, is structurally flawed. It creates steep incentive cliffs and exposes protocols to large execution costs and insolvency risk during periods of market stress. More sophisticated liquidation mechanisms, such those previously mentioned here would reduce the need for oversized incentives and shrink the window for OEV extraction. These approaches also enable smoother and more continuous risk reduction.

Even with large incentives in place, liquidations often get delayed. Perfect oracle updates are not enough as liquidations can still be delayed by slow CEX-DEX or cross chain arbitrage and limited onchain liquidity. The core challenge isn’t just disseminating the right price, it’s ensuring liquidations happen promptly and efficiently under stress.

Deeper integration with OEV infrastructure risks entrenching the current inefficiencies rather than addressing them. The DAO should be clear-eyed: OEV recapture is an optimization built on top of a flawed process, not a structural fix. Making liquidation timing overly sensitive to specific oracle updates adds fragility rather than resilience.

I’ve previously made the case here, here and here that fixing Compound’s liquidation mechanism is likely the highest leverage upgrade available to the protocol. The potential upside from such improvements should be worth several percentage points of Compound’s market cap. In contrast, OEV recapture, while helpful, is a more modest optimization that captures only a small sliver of the inefficiency while bringing its own risks and complexity.

Recommendations for the DAO

Share @cylon’s thoughts on a risk minimized rollout

+1. This is a good point to keep to mind. The protocol can always enable OEV later when the markets are more mature.

Share @Gauntlet’s views on the importance of risk mitigation

+1. This is essential. Extended liquidation delays could cost the protocol more than the additional revenue.

Platonia recommends the following approach:

- Treat OEV as a secondary optimization, not a primary feature

- Focus on longer-term design improvements to liquidation mechanisms

- Avoid vendor lock-in that could slow progress toward better architecture

- Demand rigorous empirical validation

- Vendors should provide periodic updates with accurate statistics that account for slippage, builder tips, and latency impact

- Existing OEV estimates often overstate value capture and understate or entirely omit execution costs and insolvency risk

- Prioritize protocol safety and resilience

- Fallback behaviors must be well-tested and reliable

- The DAO should carefully weigh latency tradeoffs that could introduce outsized insolvency risk

- Exclusive feed rights and auction delays require close scrutiny

- Adopt a phased and cautious rollout

- Start small across a few assets and chains, and evaluate performance before broader adoption

- Exercise extra caution on Ethereum mainnet, which accounts for the vast majority of liquidations

- Recognize that OEV is not a substitute for better long-term liquidation design

- OEV recapture should be viewed as comparable in benefit to a small reduction in SFPF

- The community should prioritize work toward more robust, capital-efficient, and user-aligned liquidation systems

Conclusion

OEV solutions present a modest opportunity to improve Compound’s revenue, but the associated risks and tradeoffs should be evaluated carefully. The DAO should proceed incrementally, demand transparent data, and avoid decisions that lock in an inefficient architecture.

Platonia looks forward to supporting the community in this discussion and helping build a stronger, safer Compound protocol!

The mainnet ETH/USD API3 oracle is omitted as it doesn’t seem to return any data for the time period. ↩︎

The mainnet BTC/USD API3 oracle is omitted as it doesn’t seem to return any data for the time period. ↩︎